[Alberto is the] shorter form of Adalberto, from Latin Adalbertus, from Frankish *Aþalberht.

– Wiktionary

The asterisk indicates that *Aþalberht is an unattested word arrived at by linguistic reconstruction.

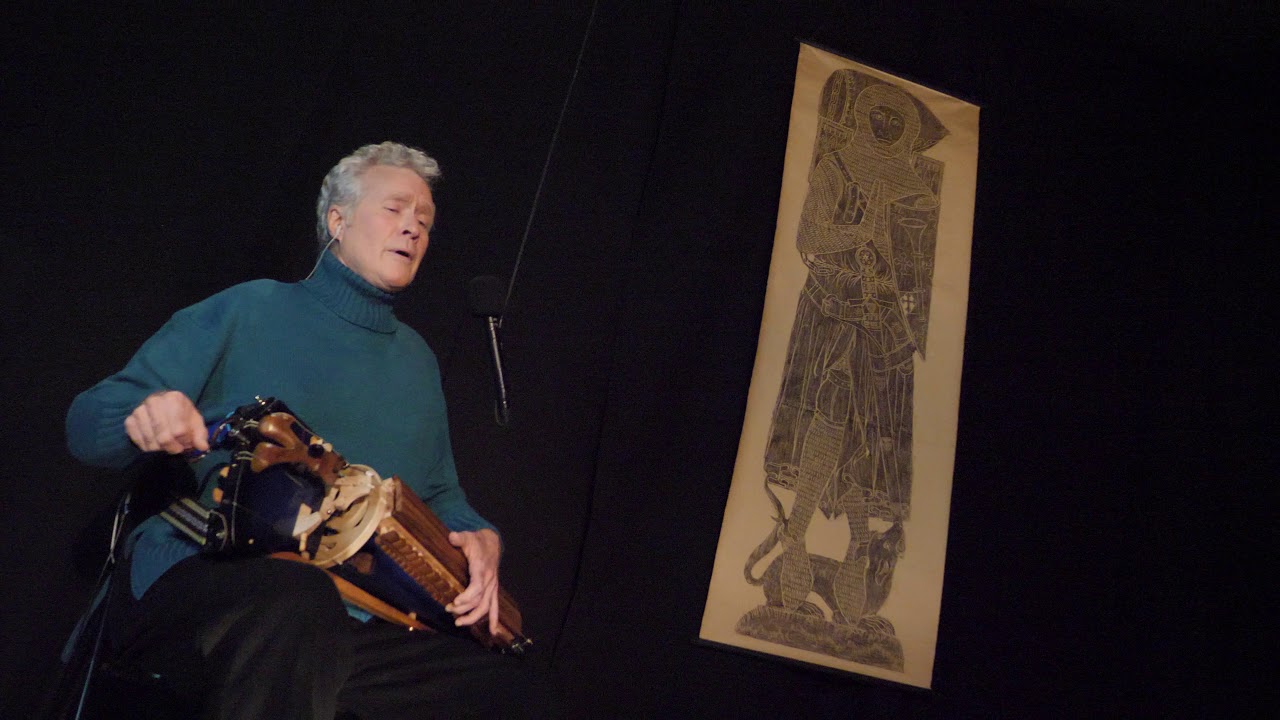

þ, the thorn, has the pronunciation /θ/, which is the th in thin (but not in that).

Frankish is an extinct West Germanic language spoken between the fourth and eighth centuries CE.

During its period as a living language, it was contemporary to Late Latin, the vague “Proto-Romance” language(s), and the early Romance languages proper, as Latin gradually broke up with the disintegration of the Roman Empire.

Frankish was also contemporary to Gothic, the most famous member of the East Germanic languages, a group that is now totally extinct. Modern Germanic languages fall into either the Western or Northern group.

So, what does *Aþalberht, and thus Alberto, mean? Like many old Germanic names, it’s a combination of two parts. *aþal is defined as “noble” and *berht as “bright, shining”.*Aþalberht is, of course, the root of not just Alberto but also English Albert and German Albrecht.

In Old English, both *aþal and *berht continued to be popular name elements. *aþal evolved into Æþel-, eg. in Æþelred. In Modern English, Æ is usually pronounced as /ɛ/ (“beg”), but would in Old English have been /æ/, which is a sort of elongated A sound, like in “bag”.

*berht often became -bert, although variant forms are also attested, like -beorht and -bryht. The Æþelbert name was revived in 19th-century England with a modernised spelling, as Ethelbert, but this name doesn’t appear to be in use any more.

We can also dig further into the etymology. The reconstructed ancestor of Frankish *aþal, again according to Wiktionary, is Proto-Germanic *aþala, with the meaning “nobility, race, nature, disposition”. The ancestor of *berht is reconstructed as Proto-Germanic *berhtaz, with the same meaning of “bright” or “shining”. Proto-Germanic was contemporaneous with Classical Latin, and received some attention from Tacitus in his late first-century book Germania.

For some context to this period of linguistic history, here’s a Crawford video discussing a section of that book, which describes Germanic culture of the time.