Long cycles of the eternal flavor

There is a huge variety of possible cycles in go. In this post I’d like to share four different ones which are kind of related to one another. I don’t have anything new to add about these - it’s just nice to collect them in one place, and maybe reach some new interested people. Also, the last one is directly connected to the Ing ko rules that @yebellz just mentioned.

Eternal life

This one is famous enough to have an established name!

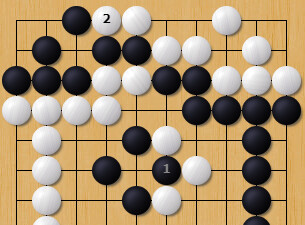

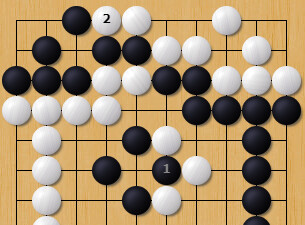

Black must prevent white from making a bulky-five, so he starts at 1. White capturing at 2 and black capturing at 3 are both forced. Finally, white has to throw in at 4 again (note that making the bulky five at that time does not kill).

If white insists on killing, and black insists on living, this cycle will repeat endlessly. Under superko rules, only 3 moves can be played locally before a ko threat is needed. Just like the triple ko in my previous post, it works similarly to a normal ko, and the side with more ko threats will win.

Here is a hard tsumego where black’s best result is eternal life:

Solution

Here is an example of Eternal life occuring naturally in a pro game from 2013:

An Sungjoon vs Choi Cheolhan (2013)

Under Korean rules, the game was voided. According to a comment on go4go, it was reported by GoGameGuru that this was the first occurence of Eternal life in the Korean pro baduk scene.

The sensei’s page on Eternal life links two more pro games which in my opinion do not fit the name “Eternal life”, I will instead call those “Eternal ko” in accordance with this sensei’s page. Another reasonable name would be “Double hot stones”, as we will see later.

Does anyone have some more examples of Eternal life happening in actual games? (pro games, amateur games, AI games?)

Eternal ko / Double hot stones

This is a curious situation where both sides can get infinite ko threats in a sequence similar to Eternal life (the similarity is in sending two returning one, but the context of the moves is quite different). To show the idea, consider this contrived position and use your imagination to pretend that the central ko is game-deciding:

When black takes the ko, white’s only threat is to play this atari:

(note that connecting on the first line would not threaten to kill the black group)

After black responds to the threat, we’re in this position:

This is where we started, but with the colors reversed! Next white can take the ko, black can sacrifice two stones as a threat, and so it continues forever. Under superko rules, if we treat the entire thing as one big ko, there would be 5 local moves between each ko threat elsewhere on the board.

Here are the two games linked on sensei’s where an Eternal ko occured:

Rin Kaiho vs Komatsu Hideki (1993)

Uchida Shuhei vs O Meien (2009)

These games were under the Japanese rules so were also voided. I recommend looking at both of them - although the idea is the same as above, the shapes are very unique and interesting.

Triple hot stones

The next two examples of cycles were brought to my attention by Harry Fearnley, and the below diagram is directly taken from this page which features some translations from a 1958 Japanese book “Igo no suri” (Mathematical Theory of Go). Please visit his page for some more historical background, I’ll just focus on the basics of the position!

On the lower half of the board we have a two stage ko. On the upper half we have something similar to earlier, except that both sides will now sacrifice three stones instead of two.

When black takes the ko, there is no threat for white, but she can prepare a threat with 2. Black’s only option is taking again with 3, and then white makes an actual threat with 4:

By now the similarity to our previous example should be apparent. Black captures three stones, and then the sequence repeats again from white’s perspective. Treating the whole thing as one big ko, there would be 9 moves (!) between each ko threat elsewhere on the board.

Quadruple hot stones

The obvious question now is, can we extend the same pattern once more? You could simply add more stages to the ko, but unfortunately we then run into the complication that one side may diverge from the sequence partway through and get a better result. It requires some additional insight to make a position where the sequence is forced for both players.

The position below was constructed by Matti Sivola and Bill Spight and published 2002 in the Nordic Go Journal:

I highly recommend reading the full article above (pages 28-30, the article is in English). It gives some background and a thorough analysis of the position which I will not replicate here.

Now apparently, this somehow relates to the Ing ko rules which tries to prevent long cycle by not allowing the capture of hot stones. The hot stones in these examples are the stones along the first line that are repeatedly captured. Since I don’t understand the Ing ko rules myself (even the simpler Ing-Spight ko rules are beyond me), I do not fully understand the context of the above construction.

I believe the existence of Quadruple hot stones was supposed to be something that the Ing rules overlooked - but I don’t know if there was a simple “fix” to this, or if the constructed position above is somehow fundamentally incompatible with Ing’s original intention.

Furthermore, since the position is constructed for (and analyzed under) the Ing rules, I’m not sure what actually happens under Tromp-Taylor. In particular, variation 2 (featuring the “disturbing ko”, one of the two types of ko under Ing rules) might lead to a different result under Tromp-Taylor. Maybe someone else wants to do this analysis for me?  Otherwise, I’ll return to it with a clearer head sometime in the future.

Otherwise, I’ll return to it with a clearer head sometime in the future.

), the trick is that we can imagine that white passes after black passes, without playing A9. So white managed to keep it open in the end, and thus scores A9 as an extra territory, giving it a win.

), the trick is that we can imagine that white passes after black passes, without playing A9. So white managed to keep it open in the end, and thus scores A9 as an extra territory, giving it a win.